Originally published at my EdWeek Teacher blog, Capturing the Spark (3/23/16).

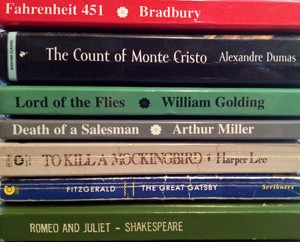

I’m genuinely looking forward to reading my next batch of sophomores’ Lord of the Flies essays – primarily, because I don’t think I’ll ever use this assignment again. Don’t get me wrong. I think there’s value for students in studying this novel, writing essays, learning some basics of different psychological theories and analyzing the novel through a psychological lens. I’m confident in the teaching and learning that are going in my classes right now, but I’ve reached my limit with this particular piece. Something has to change in this aspect of my courses.

I’m genuinely looking forward to reading my next batch of sophomores’ Lord of the Flies essays – primarily, because I don’t think I’ll ever use this assignment again. Don’t get me wrong. I think there’s value for students in studying this novel, writing essays, learning some basics of different psychological theories and analyzing the novel through a psychological lens. I’m confident in the teaching and learning that are going in my classes right now, but I’ve reached my limit with this particular piece. Something has to change in this aspect of my courses.

I started teaching twenty years ago, and for most of those years, I’ve taught sophomores. I love sophomore year. Students have completed the transition year of ninth grade, making strides in their practical, functional skills, developing the ability to navigate high school. They’re ready for an intellectual transition, a significant leap in expectations around critical thinking and creativity, and they’re not yet burdened or jaded in the ways that some of our juniors and seniors are. It’s a time ripe with potential. I have no desire to shift away from teaching sophomores.

At the same time, the arithmetic of my teaching career leads me to reconsider some of what I do. Two or three sections of tenth-grade English per year, averaging about 25 students per class, fifteen years – we’re talking about close to a thousand students (just in my sophomore classes). Close to a thousand times I’ve read similar essays about the psychology of characters in Lord of the Flies. I’ll get through one more set of essays this year, but part of the reason I’m ready to read them is that I know afterwards, it’s time to change.

Why should it matter? Why allow my feelings to factor into instructional decisions for students? Shouldn’t their learning needs be driving all decisions about the classroom?

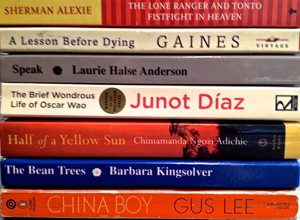

There’s a simple answer, and a more complicated one. Yes, student needs drive decisions. The next question though, what students need, is quite complicated. My students over the years have benefited from studying this novel using this approach, generating this type of work. My future students may derive the same or even greater benefits, and meet the same needs, using different materials and assessments. I can’t know for sure if I don’t try something new.

There’s a simple answer, and a more complicated one. Yes, student needs drive decisions. The next question though, what students need, is quite complicated. My students over the years have benefited from studying this novel using this approach, generating this type of work. My future students may derive the same or even greater benefits, and meet the same needs, using different materials and assessments. I can’t know for sure if I don’t try something new.

A related, and more pressing question for me right now, is this: Will my future students’ learning needs be better met by a teacher who’s more energized and engaged in learning with them? Of course. It’s more than a desire to experiment for the sake of instructional improvement; my own needs are also contributing to my decision to abandon the psychology essay for Lord of the Flies in the future. (“Put on your own oxygen mask first”). I might even give up that novel and try something new. I’ve found enough value in Golding’s masterpiece over the years to continue using it, even as I’ve changed up other aspects of my courses a little at a time. My longevity as a teacher, and my authenticity as someone who preaches lifelong learning, are both pushing me to let go of this assignment. If I hadn’t taken a year off from teaching last year, I might have made this change even sooner. Looking ahead, I know that I’ve reached my limit for how many hours and days of my life can be dedicated to reading beyond the first thousand essays.

I’m fortunate to work in a school and a district that offer enough flexibility for me to make these changes. We collaborate in framing a general curriculum for our English courses, and offer each English teacher the flexibility to approach the same skills through different texts, or to guide students through the same texts using different methods. If the time ever comes that I’m expected to teach a course I didn’t help design, using content or methods I object to, according to a timeline not designed or modified to serve my students, I’ll either change jobs or change careers. Staking out that prerogative reflects a privilege arising from my circumstances, but it ought to be the prerogative of any professional working in any school. The excessive control and micro-management of teachers, especially in less privileged schools and communities, is a largely sexist and racist tendency that we must reverse in this country.

I’m not expecting for complete individual autonomy. I crave opportunities to collaborate and co-create with my peers, to reach agreements about shared curriculum and instruction. I accept that there are external standards that guide our work (not only Common Core standards, but also National Board standards, and for English teachers, NCTE standards). I fully expect to evaluate my work myself and with peers, using evidence of student learning (NOT test scores) to guide improvements, and I expect to be evaluated by my administration as well.

I hope people who are invested in the quality of our collective teaching, our professional viability, and meeting the needs of all students, also recognize that the spark animating student learning in a classroom cannot be entirely separated from the spark that keeps teachers energized as well. And at the other end of the spark’s “life” cycle, we find burnout. With a widely recognized crisis in the making as teacher shortages grow, inspiring teachers to stay in the classroom is a completely legitimate consideration in the design or redesign of schools, courses, and curriculum.