Originally posted at my EdWeek Teacher blog, Capturing the Spark (8/24/16).

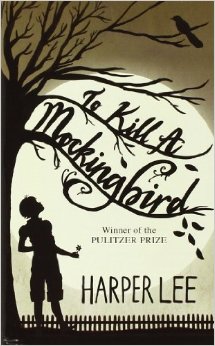

As a new school year starts, I’m reminded once again how each year presents a combination of familiarity and change. I’m teaching sophomore English classes just as I’ve done every year of my high school teaching career, coming up on twenty years. It was tenth grade that marked the turning point in my own high school experience. I clearly recall a shift in the depth and complexity of the curriculum, and began to feel like a scholar, not merely a student. Maybe that’s the reason I gravitate towards tenth grade, or maybe I just have a good grasp of that stage in students’ academic and personal development. From a practical standpoint, there’s value in teaching familiar material and not having to start from scratch. To Kill a Mockingbird, here we go again!

As a new school year starts, I’m reminded once again how each year presents a combination of familiarity and change. I’m teaching sophomore English classes just as I’ve done every year of my high school teaching career, coming up on twenty years. It was tenth grade that marked the turning point in my own high school experience. I clearly recall a shift in the depth and complexity of the curriculum, and began to feel like a scholar, not merely a student. Maybe that’s the reason I gravitate towards tenth grade, or maybe I just have a good grasp of that stage in students’ academic and personal development. From a practical standpoint, there’s value in teaching familiar material and not having to start from scratch. To Kill a Mockingbird, here we go again!

And yet, even the familiar brings something new each year, as long as the teacher stays engaged too. I’m focusing here on one book in an English class curriculum, but you might see parallels in how you approach the familiar in your own teaching. I can almost recite from memory certain passages in To Kill a Mockingbird, list the scenes in order, and offer insights regarding obscure characters like Miss Rachel Haverford and Miss Gates – and yet I find myself with new observations and questions each time I revisit the Finch family and Maycomb County. There are parts of the text I continue to wrestle with, never quite satisfied with my interpretation, or the possibility that the text may simply be inconsistent on certain matters. Harper Lee practically says family is destiny in the early chapters, but then she specifically undermines the eugenic thinking exhibited by Aunt Alexandra. Are those ideas compatible? And after doing all she can to associate the Ewells with trash, why does Harper Lee compare Mayella Ewell to Miss Maudie?

There’s ample documentation of Mockingbird‘s positive and inspirational effect on many readers and on American arts and civic life; Oprah Winfrey calls the book “our national novel.” Teaching this novel also means addressing the issue of how a white author addresses racism through the experience of white characters. That’s a perfectly valid thing to do: white readers and authors need to confront racism, though in a case like this it’s important to recognize whose point of view we’re reading and what the limitations of that viewpoint might be. The book teaches the importance of empathy, most directly when Scout is invited to stand in other people’s shoes. The invitation extends to the reader, too.

And yet, it only occurred to me this summer, as I prepare to teach the book for close to the twentieth time, that when the invitation to empathize is explicit, it’s always applied to white characters. The repeated image of standing in someone’s shoes, (or in some instances, in their skin) is suggested as a way for Scout to understand her teacher, or Bob Ewell, or Boo Radley. While the book offers a sympathetic portrayal of black characters and the black community, it never directly asks us to stand in their shoes, or skin. We are given reason to understand their pain, but not called upon to feel it. In one of his strongest statements on racism, Atticus points out that blacks are commonly “cheated” by whites, and he says that the whites that do so are “trash.” The reason not to cheat is to live up to an ethical standard for its own sake; Atticus doesn’t broach the topic of pain, suffering, or damages, nor is he apparently ready to act beyond offering a condemnation of the rampant exploitation he’s aware of. The gist of this critique isn’t original, but my awareness of the particular pattern is new.

And even if the book stays the same, the reader changes over time. As I prepare to teach Mockingbird once again, I’m still reading Isabel Wilkerson’s history of the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns. With new learning about that period in history, I’m better able to understand some of the book’s context, to answer more student questions about the institutional racism and economic oppression of blacks in the South. What used to be a general sense of “cheating” in Atticus’ comment is now specific for me, as I can explain the various ways that sharecropping and other agricultural labor practices kept black workers from gaining any economic foothold in the South. Many whites also engaged in efforts to prevent blacks from learning about opportunities to move north, and they used a variety of coercive and threatening methods to prevent blacks from moving when possible.

There’s always a risk of curriculum starting to feel stale and overused. With To Kill a Mockingbird, I don’t worry about that; dealing with rich material, staying curious about it, and adding relevant new learning all help to keep the experience fresh, even over the course of twenty years.