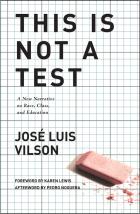

If you’ve read José Vilson’s blog posts, or articles, or follow him on Twitter, maybe you already know he can be a compelling writer and speaker. The impact of his book, This Is Not a Test, comes from both the concise, personal tone, and the direct, candid views on a variety of issues. José mixes in some original poetry (and the title of the book is derived from a poem included in the book), but even his prose is inflected with poetic phrasings and style. Click the link if you haven’t yet seen the video of José reciting his poem at the Save Our Students March in Washington, D.C. (July 2011). Even if you have seen this before, it’s worth another look.

If you’ve read José Vilson’s blog posts, or articles, or follow him on Twitter, maybe you already know he can be a compelling writer and speaker. The impact of his book, This Is Not a Test, comes from both the concise, personal tone, and the direct, candid views on a variety of issues. José mixes in some original poetry (and the title of the book is derived from a poem included in the book), but even his prose is inflected with poetic phrasings and style. Click the link if you haven’t yet seen the video of José reciting his poem at the Save Our Students March in Washington, D.C. (July 2011). Even if you have seen this before, it’s worth another look.

I thought I knew José a bit through his social media presence, through the Teacher Leaders Network (a project of the Center for Teaching Quality, where José is now a board member). We even hung out together for all of 20 or 30 minutes, enjoying a quiet conversation with Martha Infante the night before José spoke at the SOS March. But then I opened his book, and within the first two minutes, read this:

Those who have lived similar experiences to mine understand why we keep a guarded demeanor even when expressing our deepest emotions. We have an unsettling rage beneath our otherwise calm exteriors. Simply walking down the street has been an exercise in survival, even for those of us who consider ourselves nerds or outcasts. The street has taught us not to “snitch” – not because we want to protect the offenders, but because the deaths of people like Amadou Diallo show us that even our supposed protectors have something against us. So we speak in folklore, rhyme, and bombast. (2).

Whoa. Quite a prologue. For those of us who haven’t lived similar experiences, it’s an invitation to understanding, but one that promises an uneasy read. Yes, there’s folklore and rhyme, maybe a hint of bombast, along with touches of subtle humor and moments of poignancy. But this opening suggests the need to continually look beneath the surface, to remain attuned to the deeper meaning and implications of what’s presented with a “guarded demeanor.”

But aside from the stylistic qualities of the book, what sticks with me the most is clear call to pay attention to what matters most in education. It’s not a test. Drawing from his own experiences as child and as a student, as parent and as a teacher, José consistently shows how we can be built up or torn down by our experiences in educational settings. What does matter most is whether or teachers and schools can create for students an environment that is safe, respectful, academically challenging, fair, logical, stable and supportive. When discussing his elementary school experiences, José notes that his inner-city school was receiving 60% of the New York state average for per-pupil funding, but maybe receiving more than their share of motivational speeches by a visiting “semi-famous person or company.” The hypocrisy of sending rhetoric instead of adequate resources speaks for itself, though Vilson suggests the school had a positive atmosphere despite the challenges. Then, he speculates, “Had our current heightened accountability measures been in place then, they would have likely snipped the warm-and-fuzzies I felt walking down those hallways. The school building may feel the same and the classrooms may not have changed much, but can a school preserve a warm environment when it is beholden to the cold calculus of keeping up test scores?” (24).

José’s experiences as a child inform his thinking and advocacy quite a bit, but he’s smart enough not to assume his past reveals “the truth” about learning or teaching for everyone else. In fact, he parodies such thinking in one passage in the book, inventing (or, not?) teachers who cite their own successful school experiences as evidence to support their own practices. “When I was a student, my teacher used to draw lettuce next to the most important points of her notes and that worked because I could identify with lettuce…” (25). At the same time, however, José offers some specific examples of how sharing cultural and linguistic backgrounds with his students gives him an advantage at times; they use Spanish cognates to learn math, compare experiences growing up, use lines from rap and hip-hop songs to form a bond. It’s not a claim of exclusivity, that black or Latino teachers alone can be truly effective in reaching similar students, but rather a question of using what you have in common as a foundation for relationships and learning.

The occasional use of poetry adds to the book in a powerful way. José writes about a former student murdered at the age of 15, and pulls us along “into a funeral home I’ve seen all too often,” where

The naive become adult, the short get closer to the heavens

The elder get greyer and the insolent gain wisdom

While mothers and daughters yell like fishing rods that never capture their catch

This observer’s pupils dilate

Inspiration to proceed with his daily occupation… (91)

José’s book is also interesting in its treatment of educational leadership and education technology. He questions the “faux expertise” among (non-specific) self-proclaimed leaders in “ed-tech” (“I roll my eyes every time someone invokes the term”). But beyond the rhetoric or puffery in this crowd of individuals, José questions “the flimsy nature of current technology. Everyone needs to have all of the answers, do all of the things, be in all of the conferences, and put all of it in their social-media profile, even as they are learning along with the rest of us. …The more new things come out, the more techies who feign relevance need to stay current – but to what end? If the students, teachers, or parents don’t actually see value in taking time to implement this new thing, why pretend expertise?” (138).

The technology questions fold into discussion of race and privilege as well. Who gets to set the topics of conversation and the rules of engagement when we talk about education? As pedagogy and technology spin off in new directions to the excitement and delight of many educators (and tech vendors), José questions

why people at the [EduCon] conference and in my daily interactions in education spheres thought the immediacy of ed-tech mattered more than ameliorating race relations in this country. Do SMART Boards and iPads really change pedagogy for the millions of of students institutionally ostracized based on their race, religion, or gender? Or are they merely Band-Aids that can be used to say, “Oh look, we did something and we never had to get our hands dirty to make it happen”? I also know that, ultimately, one can’t force others to change their behaviors; they have to believe in that change. (149)

The imperative to address equity occurs, or should, at multiple levels: José touches on many more issues of policy and practice, where certain schools and certain teachers are marginalized, and where teachers themselves are marginalized, largely as a function of being part of a predominantly female profession. (See Part Three, “To Make Sure It’s Broke (On Teacher Voice)”).

But near the end of the book, José brings the narrative back to something more elemental, essential, foundational to everything else we wrestle with in the public sphere, as he writes movingly about the calling, the feeling of being a teacher: “Teaching has given me no choice but to activate my best inner qualities and to accept and embrace that I will never stop being a student myself. I love that every day there’s a new set of problems for me to solve. Even as I’m teaching my kids math, I’m learning along with them” (214).

I would hope, and expect, that This Is Not a Test will activate the best qualities in anyone who reads with curiosity and empathy. Though, it activated one other feeling for me, which I’ll explain with a parting anecdote.

About ten years ago, author Gus Lee came to my sophomore English classes to discuss his novel (a thinly veiled memoir) China Boy, and to talk to students about writing and life. He recalled working on the manuscript for his novel about finding his identity as the American-born son of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, and then reading the brand new novel by Amy Tan, The Joy Luck Club; he was devastated (his word) by how good her book was in relation to what he had only begun.

Now I understand Lee’s reaction a bit more than I used to; I’m not “devastated” – but I read This Is Not a Test at a time when I’m embarking on a writing project of my own. Like Gus Lee did, I have a glimpse of something fresh and relevant that precedes my work and raises the bar a notch or two.

There are plenty of good education books out there, and of course a steady stream of articles and blog posts to inform us. Many wise and wonderful people are sharing insights and advice, and often their work leads me to question my own thinking and practices. Few books push me to think quite as deeply about who I am, and how significant a role identity plays in teaching and public life. José Vilson’s book accomplishes that, and left me grateful for the reading experience.

My own writing project involves traveling all over the to visit and write about great teachers in California’s public schools. You can support that work, and get a copy of the book I’ll write, by visiting my Kickstarter page before 11 p.m. Friday, Nov. 14.

One thought on “Book Review: This Is Not a Test, by José Vilson”