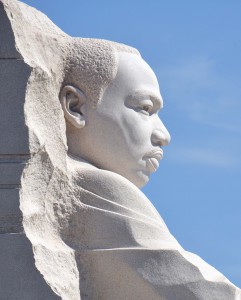

Closeup of Stone of Hope. Photo credit: NPS/volunteer Bill Shugarts. Public domain.

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing, and around the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday, you can find any number of people pulling a few MLK quotes to fit their political point of view, and never mind the bigger picture.

Admittedly, I didn’t read many articles on MLK Day this year, but here’s one that was a doozy:

[Derrell] Bradford: Have All Those ‘White Moderates’ Martin Luther King, Jr. Decried From Jail Become Today’s Anti-School Choice Progressives?

In his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King called out clergy and white moderates whom he believed may have had decent intentions and sympathy, but a lack of will to take risks and fight for true equality. In debates around public education, where it is particularly evident that our society has failed to address the needs of children of color and children in poverty, both sides like to lay claim to the legacy of Dr. King as a way of arguing the righteousness of their viewpoint. It’s predictable enough that José Vilson addressed it in his recent piece: Read This Before Co-Opting MLK Jr.

Well, over at the education “reform” website known as “The 74” someone went and co-opted MLK Jr., big time. Derrell Bradford was the author – he’s the director of the New York Campaign for Achievement Now – essentially a political lobbyist working in education reform despite having no education background (surprise!). No surprise either that The 74 published his take on MLK’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, in which modern progressives who oppose corporate education reform have become the new version of “the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice” (King’s words).

Bradford’s piece fails on two fronts. First the overall concept is flimsy. He wants to lay claim to King’s legacy by using a few quotes, but without examining King on the issues. Was King in favor of school choice? I don’t think he ever addressed that issue directly, but we do know that current trends in choice and charters are increasing segregation, and I’m pretty sure Dr. King was mostly, not really in favor of that. If charters were proven to be the gateway to better education and greater social equality, the argument might make sense, but that’s far from settled too. Bradford’s claim to MLK is undone by faulty logic, trying to extrapolate a position not supported by evidence. And as I’ll show momentarily, it’s not hard to find another King quote to skewer Bradford’s argument.

Setting aside the failed attempt at seizing the MLK high ground, we are left with a shoddy piece of charter school rhetoric that’s weak on logic and facts. Here are a few egregious examples.

“Have the white moderates [King] spoke of then turned into today’s white progressives who oppose change in education?” Bradford sets up a straw man here. No one defends the status quo. Opposing bad ideas based on their flaws is not inherently defending the status quo, any more than suggesting that someone not put out a fire with gasoline.

Bradford writes: “both the anti-testing (opt-out) and anti-charter movements… trouble me deeply. [They] send a clear message to minority families about who has the power to make government responsive and who doesn’t.” To make sense of this statement, understand that Bradford sees the opt-out movement as largely driven by white middle and upper class parents. In some places, maybe it is. But who’s guilty of marginalization now, with Bradford unaware of, or conveniently omitting the students, families, and educators of color around the country, who opt out because they see testing policies as a part of a political strategy to disenfranchise them? Bradford’s frame for this national discussion seems to be New York alone, based on his examples. For what it’s worth, the United Opt-Out national leadership is a heck of a lot more diverse than the all-white board of directors at The 74. The students, teachers, speakers, writers, and activists highlighted on Jesse Hagopian’s blog are don’t look much like the people Bradford attempts to shame, either.

Bradford believes that standardized testing is one of education’s “pillars of equality and freedom” because “Without this objectivity and information, we have a world that’s inherently unfair and deeply unequal.” I’ll agree that we need some form of accountability that prevents educational systems from ignoring populations of students, and NCLB’s requirement for subgroup reporting was one of its few successes. But it requires a huge leap of faith to believe the testing policies that spurred the Opt-Out movement were going to deliver equality, freedom, or fairness. We have, however, seen test score-based policies instead narrow school curriculum, close neighborhood schools serving mostly students of color, displace veteran teachers and teachers of color, and stigmatize schools, teachers, and students over the effects of inequity, by mistaking the effects for the causes.

Bradford: “income inequality… is pervasive in large measure due to educational disparities.” Here the author takes a situation that is incredibly complex, and offers not one example or study to back up this bold claim. If every high school student in America were to graduate from high school college and career-ready, would we have good enough jobs to generate wages and salaries that would make a dent in income inequality? Not likely. And would Martin Luther King, Jr. have endorsed Bradford’s view? Also unlikely. In 1967, Dr. King wrote about solving the problem of poverty, and noted that focusing on education, housing, and welfare had not worked in the past, and likely wouldn’t in the future:

In addition to the absence of coordination and sufficiency, the programs of the past all have another common failing — they are indirect. Each seeks to solve poverty by first solving something else.

I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.

But for the education reformers who love them some civil rights (gift-wrapped in corporate control of schools, technology, curriculum, testing and data services), Bradford’s position is more appealing, and has distinct advantages: there’s no mandate to engage in messy political fights for higher taxes or shifting budget priorities away from the military, for example. No battle for better health care, living wages, expanded public housing and transportation, or any tax increases that might help us address some of the effects of poverty. Would it be overly cynical of me to point out that many backers of the charter and choice movement might derive some income and profits from their preferred solutions, while the broader socio-political approaches I suggested could have a negative (short-term) impact on their earnings?

One final straw-man from Bradford: “The freedom unleashed by ‘the right to choose’ is so transcendent there are those who wish to keep it close and who oppose many parents—black, brown or otherwise—having it at all.” Again, Bradford chooses battle with the privileged whites because, with MLK on his side, rhetorical victory is assured, right? But if you’re “black, brown, or otherwise” and you aren’t embracing charter schools, you’re not part of this debate. The real straw-man element of this argument is that charter school opponents aren’t against this vaguely defined “right to choose” but rather, opposed to the means by which this choice is manufactured and sold, and the costs it imposes on the general public.

You have to admire Darrell Bradford’s imagination though. He’s cooked up a political world view in which he’s The True Progressive, and his agenda still aligns with some wealthy, white, right-wing conservatives who are just progressive in this one area – and Dr. King is right there with them in spirit.